In response to the Protestant Reformation, the Council of Trent was convened to examine doctrine and reform of the Catholic Church in various sessions between 1545 and 1563. One point of these sessions was to discuss the responsibility of religious images. During this period, the influence of the Council was very distinct compared to that of the Renaissance. The Renaissance era valued a simpler, more philosophical beauty in the portrayal of biblical works. They left patrons and supporters to consider and stipulate about what was occurring in the world of art. With responsibility bestowed on Catholic followers, the art of the Baroque era had a precise reason and focus for art. And that was to draw out emotion. Art had a greater impact than just the spoken word. It was a valuable instrument for inspiring devotion and teaching doctrine of the church. And that was achieved to an amazing degree with master painters of the Baroque era.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was an Italian Baroque painter, who before and after being a well-known artist, led a wild life. He was known for his temper and fighting leading to jail numerous times for some serious offenses. He managed to see his way through the consequences of such behavior. The influential Cardinal del Monte was instrumental in Caravaggio’s career progression once the artist was a part of his court after 1595.

The church was aggressive and strict in what they expected from the people. Art, during this period, was meant to evoke emotion and a religious commitment in its sponsors. With the Catholic court’s support and guidance, Caravaggio understood the church’s direction and expectation for artists.

Caravaggio’s extreme level of realism was barely appreciated by fellow artists. The scholars within the Council of Trent wanted art to be more natural than the Mannerist visions of the fading High Renaissance style. But Caravaggio had his own visions. Visions that went well above the Council’s or any other supporter’s imagination. At the time, artists were encouraged to represent religious subjects in a reachable way, with clarity and sense of closeness, to connect viewers directly with the sacred subject. Caravaggio’s work went past the frame. It reached (and still reaches) the viewer through his emphasis on co-extensive space or feeling part of the scenery (see The Supper at Emmaus).

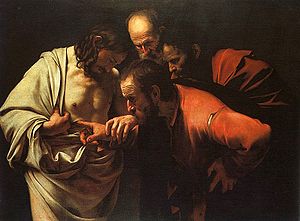

Using various techniques from the Renaissance period, tenebrism and chiaroscuro, Caravaggio shows everything, from grimy fingernails, to the callused bottoms of feet (see Madonna di Loreto) and to bruised fruit with worm holes. It was like photorealism from his own era. And The Incredulity of Saint Thomas represents Caravaggio’s ruthless honesty. Only someone who associated with the simplest and poorest people of Rome could extract the realism of everyday life and incorporate it with biblical subjects.

In The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, Jesus grabs hold of Thomas’ hand and places it inside the wound of his body in order to remove doubt from Thomas. Caravaggio does the same for his viewers until we believe, just as Thomas began to believe. Again, the artist places his emphasis on co-existing as well. It seemed as though Caravaggio, understanding he was a sinner, could interpret Christianity better than anyone. He lived the life. He knew the life. Caravaggio was the vessel the Council had in mind when seeking artists depicting stories through art presented with clarity, realism and emotion. The Council of Trent wanted to restore the church in its place of authority and convince people that they were not the bad ones. Consequently, Caravaggio wasn’t too concerned about being the bad one. He took it on head on and with full force through his art and life.

References:

Samworth, Herbert. The Trent Council: The Roman Catholic Church Response to the Protestant Demand for Reformation of the Church (1545-1563). Sola Scriptura, Grace Sola Foundation. Web. 19 June 2015. http://www.solagroup.org/articles/historyofthebible/hotb_0010.html

Tenebrism: Characteristics of 17th Century Tenebrist Painting Technique http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/painting/tenebrism.htm

“Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da (Italian painter, 1571-1610)”. Getty.edu. Retrieved 19 June 2015. http://www.getty.edu/vow/ULANFullDisplay?find=Caravaggio&role=&nation=&prev_page=1&subjectid=500115312